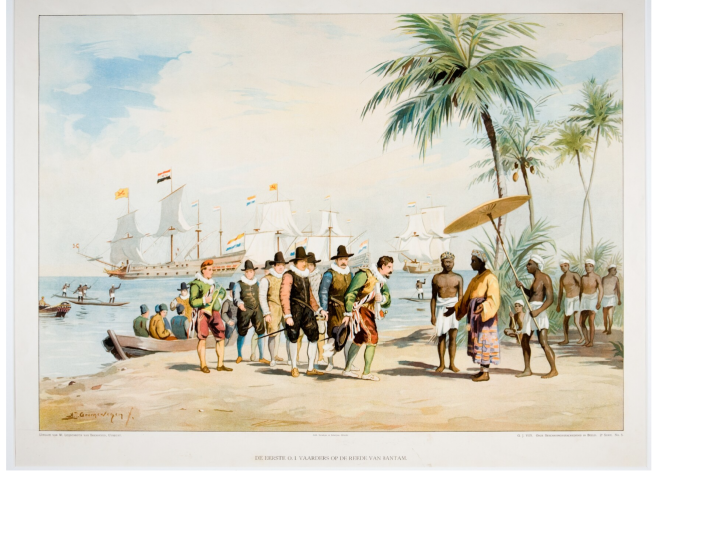

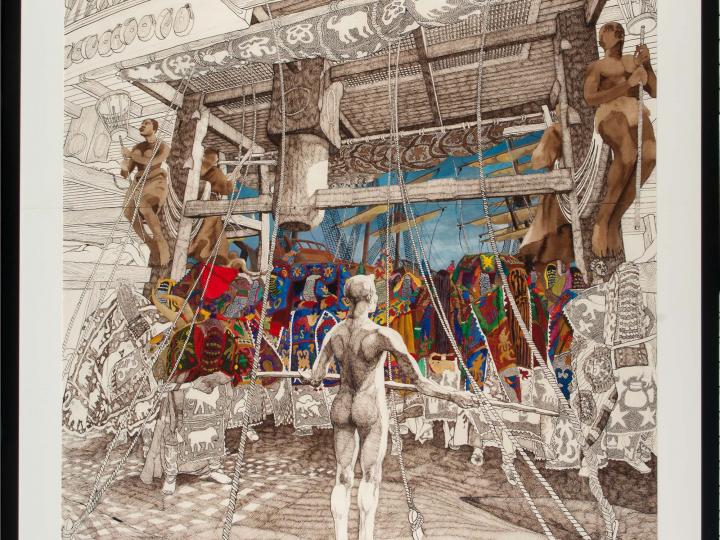

The trade in spices and other goods was extremely lucrative, but the Dutch also faced fierce competition from Portuguese, Chinese and Indian merchants. Initially they were also forced to go along with the trading conditions imposed by local rulers. The two big trading companies, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and its sister organisation the West India Company (WIC), built up an international network on the back of existing trading networks, often securing power and trade by force. From the beginning there was local resistance in response to Dutch aggression.

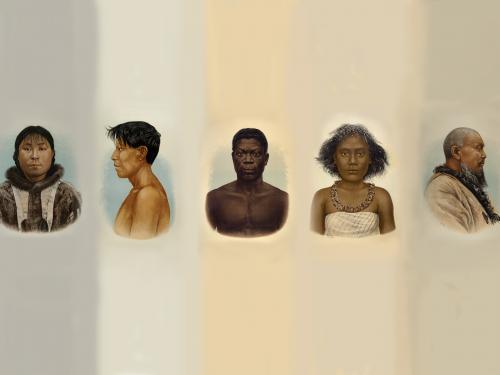

A central aspect of colonialism was slavery. The European colonizers forced people to work for them in both Asia and Africa, as well as in North and South America. They enslaved people and bought and sold them on an appalling scale. As such slavery formed the foundation of what was to burgeon into an international colonial network.